About

ABOUT

ABOUT THE YAMASHITAS

The Yamashita family was one of the thousands forced to leave their homes in the months following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and spend World War II behind barbed wire. Like many families, they were separated by their incarceration: the father, Gihachi, was detained by the FBI just hours after the attack and subsequently held in a number of internment camps; the mother, Tsugio, and two daughters, Angela and Lillian, were forced to pack up their belongings and sell their property, and they were eventually incarcerated in a concentration camp miles away in Arkansas without Gihachi.

The experience of Tsugio, Angela, and Lillian is the more common one among Japanese Americans on the West Coast of the United States. There were nearly 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry incarcerated in ten concentration camps in the US interior for most of the war; two-thirds of those incarcerated were US citizens.

Several thousand others were held in smaller camps run by the Department of Justice, like Gihachi. Why was he held separately? Who decided to put him there and why? Why were Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II at all?

Decades later, in the 1980s, following years of pressure from grassroots groups, politicians, and legal experts, the US government created an independent commission that investigated the wartime incarceration. The commission concluded that the incarcerations—both the more common type experienced by Tsugio, Angela, and Lillian, and the less typical one experienced by Gihachi—were based not on real threats but racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.

In 1988, Congress passed a bill to formally apologize for the wartime treatment of Japanese Americans and pay reparations to each person incarcerated. It also set up a fund to support efforts to educate the American public about this injustice, helping to ensure it never happens again to Japanese Americans or anyone else.

Dad: Gihachi Yamashita

Gihachi was born in 1888 in Mie, a small prefecture in western Japan best known for being home to one of Japan’s most important Shinto shrines. We know little about his childhood. He left his hometown in 1906 and traveled to Tokyo, where he attended high school before departing for the United States in 1907.

Gihachi entered the United States through the Port of Seattle and lived the life of a laborer for at least the next decade. He worked on farms and railroads throughout the Intermountain West. In 1921, he briefly went home to Japan so that he could marry. He returned to the United States with his new wife, settling first in Salt Lake City and eventually Los Angeles, where he found work as a janitor for an automotive firm downtown.

Mom: Tsugio Yamashita

Tsugio, like Gihachi, grew up in Mie Prefecture. We don’t know much about Tsugio’s childhood either. In 1921, Gihachi and Tsugio married in Mie. It is possible that this marriage was arranged by people who knew them both, as this was common practice, or perhaps Gihachi met Tsugio when he returned to his home village. Once married, they went back to Gihachi’s adopted homeland. When they relocated to Los Angeles, Tsugio managed a hotel in downtown Los Angeles.

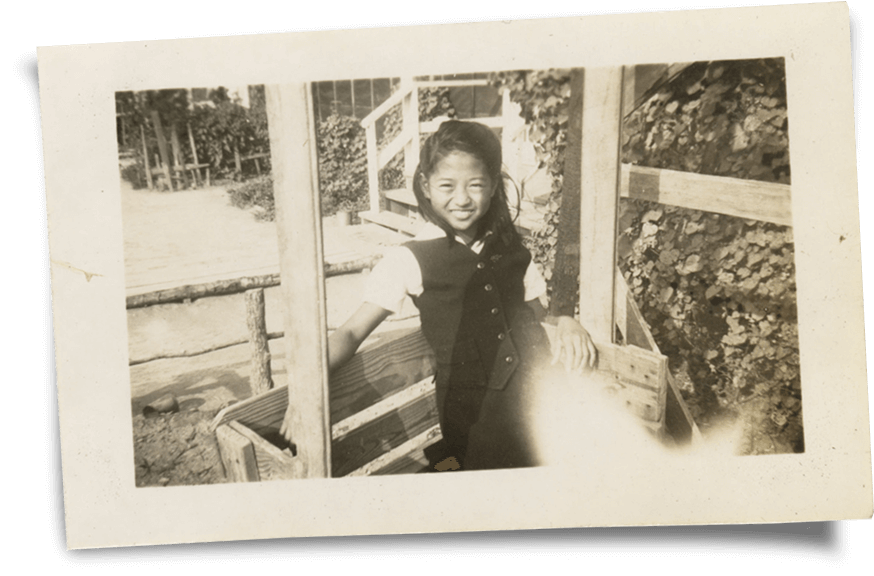

Daughter: Lillian Yetsuko Yamashita

Lillian (whose Japanese name is Yetsuko) was 13 when the FBI detained her father. She spent most of her teenage years in Rohwer, one of the concentration camps in Arkansas.

Daughter: Angela Yukiko Yamashita

Angela (whose Japanese name is Yukiko) was 11 when her father was detained.

ABOUT THE TITLE

“Enemy Mail” refers to the way Gihachi Yamashita’s correspondence was classified by the US government during World War II. It was called “enemy mail” because he was categorized as an “enemy alien,” a subject of a nation with which the US was at war. But when you look at what he wrote about in his letters, it is hardly dangerous or hostile. Gihachi mainly wrote to his wife and daughters about everyday things: what he was eating, how he spent his time, his concerns about how his daughters were growing up. He sometimes wrote to let his wife know he was sending her things or to ask her to send him things he couldn’t get on his own.

ABOUT AMERICAN INTELLIGENCE COLLECTING BEFORE WORLD WAR II

The intelligence agencies responsible for judging the potential dangerousness of Japanese immigrants had no Japanese specialists or anyone who knew or understood Japanese immigrant communities on staff. These agencies determined guilt and suspicious activity based on supposition, assumption, and stereotypes. To be associated with a group considered suspicious was often all it took to be placed on a surveillance list. The Department of Justice created three categories: the “A list” was for those considered potentially dangerous; the “B list” was for those who were less threatening; and the “C list” included people like Gihachi who were deemed suspicious for maintaining ties to their homeland.

Why was Gihachi under suspicion?

Gihachi’s case is an excellent example of how stereotypes and vague suspicions can replace evidence of wrongdoing in a time of fear and uncertainty.

Gihachi’s records, now available at the National Archives, give several reasons for his inclusion on one of the so-called “A-B-C” lists.

Like many other immigrants, Gihachi was active in his prefectural association and had even served as the Mie prefectural association treasurer. These prefectural associations brought together people from the same places in Japan, offering them a sense of belonging and comfort in a new and foreign land. The groups also occasionally donated money and supplies to Japan in times of emergency and urgent need, like after the Great Kanto Earthquake that devastated Tokyo in 1923. After Japan started its war against China in 1937, the prefectural associations sent relief to war widows and orphans. Such activities put them under suspicion in the United States.

A second group that appears consistently in Gihachi’s records is the Kaigai Kaigun Kyokai, or Overseas Naval Association. The US government thought this group was actively supporting Japanese military activities by surveying the maritime capabilities of competing powers. However, this is doubtful; the intelligence agencies’ beliefs about this group were based more on supposition than on facts or empirical evidence.

ABOUT THE ROUND-UP OF ENEMY ALIENS AFTER PEARL HARBOR

Gihachi Yamashita was one of more than two thousand Japanese Americans on a government surveillance list—mostly, but not exclusively, Issei (first-generation) men—who were rounded up by the FBI in the hours and days following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Unbeknownst to most of them, they had been under surveillance before the war and were considered potentially dangerous “aliens” because of their occupations, membership in certain immigrant organizations, or relationships with Japanese dignitaries, military officers, or government officials. The list included Buddhist priests and missionaries of a number of new Japanese religions like Konkokyo or Tenrikyo that were associated with Shinto; editors of Japanese-language newspapers and teachers at Japanese-language schools; and those who, like Gihachi, owned businesses, organized welcoming celebrations for visiting Japanese dignitaries, or worked for Japanese consulates. Those under surveillance were, in other words, pillars of Japanese American society; many were decades-long residents in the United States and were and well respected by their communities.

We now know that none of these people were ever found guilty of any acts of espionage or subversion. But in a time of war, the mere association with ideas and groups considered dangerous was enough to suggest guilt.

As was the case with Gihachi, FBI agents appeared on the doorsteps of these Japanese Americans’ homes in the hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, when uncertainty and fear gripped everyone in America. Often, the agents did not offer much of an explanation and simply apprehended their targets. Wives and children were left behind; business associates and friends had no idea where these people had been taken, how long they would be gone, or what their fates might be.

Those arrested just after the bombing of Pearl Harbor dealt with their own uncertainties and fears. Again like Gihachi, they were usually taken first to a local jail and then transferred to an immigration detention center. Eventually, they were sent to one of the internment camps administered by the Department of Justice, like the one Gihachi was sent to in Missoula, Montana. For a brief period, the military took over custody of the internees, and they were transferred to military-run camps like Fort Sill and Fort Livingston. Eventually, by March of 1943, the Army returned their internees to the Department of Justice. This is how Gihachi ended up at Santa Fe Internment Camp, which was operated by the Department of Justice.

Between December 7, 1941, and early spring 1942, Japanese Americans on the West Coast faced growing hostility and animosity from neighbors as their own fates remained uncertain. They eventually confronted the prospect—and then the reality—of being forcibly removed from their homes and incarcerated in barren environments, far from home and without the leaders of their communities.

ABOUT DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE INTERNMENT CAMPS

The men (and few women) in the Department of Justice camps were almost all Japanese subjects; at the time, US law did not allow Asian immigrants to become naturalized citizens. Long before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI, the Office of Naval Intelligence, and the Army’s Military Intelligence Service, together with the White House, had discussed what to do with immigrants considered dangerous in the event of war. Plans were put in place to coordinate among the different agencies involved in the apprehension, detention, and assessment of these potentially dangerous “aliens.” The criteria for assessing this threat was tenuous and vague—membership in a Japanese chamber of commerce or prefectural association was often considered incriminating enough.

One reason the US government devoted considerable energy to creating procedures for detaining Japanese immigrants was their concern for the American prisoners of war (POWs) held by the Japanese. Soon after the United States entered the war, it publicly announced its intention to adhere to the terms of the Geneva Convention in its treatment of civilian internees. This was presented as a good-faith gesture to Japan with the hope that Japan would reciprocate. The application of the Geneva Convention in the different Department of Justice camps—and, while they were in operation, the army internment camps—was uneven and imperfect. But the internees, who learned early on that their imprisonment was supposed to comply with the Convention’s standards, relied on it to protest any harsh or improper treatment in the camps.

Separated from their families, congregations, business associates, and friends, internees in the Department of Justice camps fought isolation, loneliness, and fear. But at the same time, the peculiarities of the legal status of these camps—and the application of the Geneva Convention—also created unique circumstances and freedoms not present in the camps in which most other Japanese Americans were incarcerated.

ABOUT THE YAMASHITA COLLECTION AT JAPANESE AMERICAN NATIONAL MUSEUM

This invaluable collection of letters, diaries, scrapbooks, and objects provides us with an intimate view of a family detained. But even more, it reveals the resilience of family bonds and the human spirit. It includes Gihachi’s reflections while separated from his family, letters between Gihachi and his wife and daughters as they reached out to each other through months and years of fear and anxiety. It shows how communities were rebuilt and reshaped within the confines of different sites of incarceration.

The fact that this collection survived and is now preserved as part of the Japanese American National Museum’s permanent collection is a testament to the determination of this family to persevere in the face of unimaginable hardship.

ABOUT THE STORIES

The stories told on this website come from several different types of sources: Gihachi’s journal, written in Japanese; English-language letters Gihachi sent to his wife and daughters; and Japanese-language letters he sent to his wife alone. There are also a few letters sent from US government agencies to all members of the family.

ABOUT THE JOURNALS

Diary-writing is a time-honored tradition in many cultures. While we tend to associate this act with recording the personal details of our lives, it is important to remember that diaries are often not private, and sometimes not even intended to be. Social media is only the latest version of this public sharing of private lives; throughout the history of many different cultures, people have kept diaries with the intent of finding an audience.

We cannot ask Gihachi what he intended to do with the diary he kept between his incarceration in Missoula and his transfer to Santa Fe, but there are some clues that suggest he meant to share it with others eventually. The first clue is his penmanship. We have two other notebooks from the same period, full of what seem to be drafts of speeches—maybe assignments from a speechwriting class—that are much harder to read. His journal, however, is written very clearly and carefully. The other notebooks seem to contain things he wrote just for himself, that didn’t need to be read by others. The noticeable difference in penmanship suggest a concerted effort to write legibly in the journal and thus ensure it would be readable to others.

The second clue is in his style of writing. Gihachi begins his journal on January 22, 1942, but starts by recounting the events of December 8, 1941, when he was arrested by the FBI. In other words, this is not just a daily record of events that happens to begin on January 22 but a careful recounting of his personal experience of being apprehended and detained. He starts by saying he will never be able to forget these things, as though he is beginning a long story. This is Gihachi’s history of World War II, told from within the internment camps, with an awareness that his experiences are part of a bigger, more significant narrative.

The last clue is one curious feature of the journal. There is some inconsistency in the dates, and Gihachi’s account of the death of a Japanese immigrant from Panama in his camp is told twice. This suggests he may have written about certain events days or even months after they happened but tried to date them accurately, based on his memory.

We don’t know for sure, but we can make a fairly good guess that Gihachi understood the significance of the historical moment in which he was living and decided to create an account of his own experience of it as it was happening. Perhaps this was one way he found to make productive use of his time in the camps or maybe this was a way for him to feel connected to his family, by recording experiences he may have hoped to share when they were reunited. Seventy-five years later, we benefit from his efforts because they help us gain insight into this distant time.

PRODUCTION CREDITS

Project Team:

Thomas Gallatin

Kelly Gates

JoAnn Hamamura

Jamie Henricks

Sergio Holguin

Evan Kodani

Monica Koyama

Vicky Murakami-Tsuda

Allyson Nakamoto

Leslie Unger

Maggie Wetherbee

Lynn Yamasaki

Project Consultants:

Stacey Allan, Copy Editor

Emily Anderson, Scholar and Translator

Zumwinkle.com, Web Design & Development

Additional Thanks: Katie Yamasaki

ABOUT JANM:

The Japanese American National Museum (JANM) was established in 1985 and is the largest museum in the United States dedicated to sharing the experience of Americans of Japanese ancestry. It is located in the historic Little Tokyo district of downtown Los Angeles.

The mission of JANM is to promote understanding and appreciation of America’s ethnic and cultural diversity by sharing the Japanese American experience.

We share the story of Japanese Americans because we honor our nation’s diversity. We believe in the importance of remembering our history to better guard against the prejudice that threatens liberty and equality in a democratic society. We strive as a world-class museum to provide a voice for Japanese Americans and a forum that enables all people to explore their own heritage and culture.

We promote continual exploration of the meaning and value of ethnicity in our country through programs that preserve individual dignity, strengthen our communities, and increase respect among all people. We believe that our work will transform lives, create a more just America and, ultimately, a better world.

The material on this website is based upon work assisted by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

The material on this website is based upon work assisted by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

This material received Federal financial assistance for the preservation and interpretation of U.S. confinement sites where Japanese Americans were detained during World War II. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability, or age in its federally funded assisted projects. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to:

Office of Equal Opportunity

National Park Service

1849 C Street, NW

Washington, DC 20240